In judging the impact of sku or parts count reduction on a manufacturing company, it’s the sku count that is the organizational killer.

Each newly created sku has to be designed by either in-house or a supplier’s engineers, or perhaps it can be selected by a design engineer from a supplier catalog if it is a standard part such as a ball bearing or common fastener.

If the new sku is to be produced in-house, then the company’s design engineer(s) collaborates with the company’s manufacturing engineers and industrial engineers to design the production process for the part, and select or design or buy production machines, tooling, jigs, and fixtures to produce the part. The industrial engineers have to design the work cell or line, and estimate the manpower (if any) required to produce the part in the required volume. After selecting and purchasing the required raw materials, shop floor workers have to be trained, and the new production process has to be tested for production rate and quality adherence. This entire process takes skilled professional staff, time, and money.

On the other hand, the new part(s) can be sourced from the company’s traditional supplier base, where a prospective supplier has to go through exactly the same process described above.

But one doesn’t usually just specify a supplier (unless they are pre-qualified, i.e., a current supplier). A team of people including a purchasing agent, perhaps a manufacturing engineer, and a quality engineer have to physically or virtually visit a potential supplier to qualify a supplier with regard to the supplier’s demonstrated and continuously monitored quality levels, its routine production capacity and ability to meet required volume levels – as well as its “flex” capacity, its ability to smoothly schedule its operations, its suppliers’ capacities, its information technology and networking capability, and the like.

If the supplier is qualified, then price and delivery negotiations can start. Perhaps no one supplier can do the job, so two qualified suppliers have to be lined up, if for no other reason than to play the two suppliers off against each other in a competitive bidding process. In any event, one can easily see that this procurement process takes a lot of time and costly overhead, per sku! Thus, does an organization grow……………and grow more complex and costly unless constant attention is paid to sku and parts count reduction. As Elon Musk’s vertical integration strategy dictates, Tesla’s high degree of vertical integration eliminates a lot of this wasted effort, time, and cost by minimizing the number of Tesla’s outside suppliers.

It is to a company’s advantage to use group technology principles to find an existing sku that only needs a simple modification rather than a complete design from scratch. Likewise, it is sound practice to re-use existing parts when possible, with the exception of when the part is customer-facing. How many years, if not decades, has GM used the same turn signal/windshield wiper/washer stalk in its vehicles despite multiple brand price levels and model styling changes? How boring and lacking in innovation, and a sure indication to customers that the bean counters are in charge! It’s possible for a company to carry its parts reduction campaign too far.

So sku/part count reduction comes down to two rules: 1) maximize parts usage per sku and 2) there is more leverage in cutting skus, due to rule 1 above. Skus can be cut by an analysis of inventory turns, and/or the use of group technology software, in addition to implementing quick-review policies that encourage designers to justify the creation of every new sku.

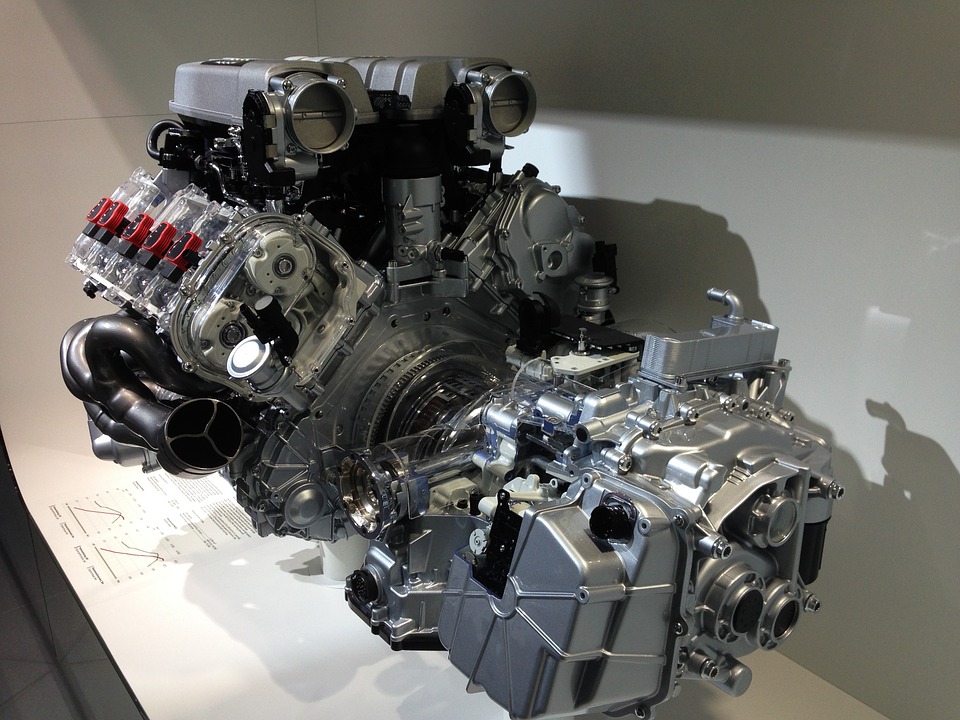

Let’s bring the discussion back to electric vehicles versus ICE-powered ones. I am not aware nor do I have access to any accurate parts count comparison studies of electric powertrains versus ICE-powered powertrains. I am sure Sandy Munro’s Munro Associates and other consulting firms have performed these teardown analyses, but they are not available to the general public. That being said, I don’t think the 20 to 2,000 moving parts ratio for electric vehicle motor/drive units to ICE-powered vehicle engine/transmissions is realistic or valid. Let’s simplify things by eliminating the “moving” qualifier. I am comfortable with 1,600 to 2,000 parts (not skus!) for the combination of a six or eight cylinder typical auto engine and a conventional 8-speed automatic transmission. That number is at least in the ballpark.

In my estimation, the reputed number mentioned above for battery-powered electric vehicles’ motor/drive units doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. [As an aside, the battery packs for Tesla’s EVs contain some 4,000 plus cylindrical battery cells apiece.] I suggest that you watch a teardown of a Tesla motor/drive/inverter unit on YouTube and check out all the skus/parts in it. Furthermore, we are assuming we count just one such motor/drive/inverter unit for a rear wheel drive-only version of the vehicle. OK, so maybe we should just count skus per type of vehicle!

Discounting the battery pack, I think one could make the case for a 75% reduction in ICE engine/transmission versus motor/drive/inverter unit parts in going from an ICE to electric-powered vehicle. So instead of 2,000 down to 20 “moving parts”, it’s more like 1,600 to 2,000 down to 500 parts. On an sku basis, maybe a 60% reduction for ICE engine/transmission to an EV motor/drive/inverter unit is reasonable. This is still an incredibly significant parts/sku, cost, and complexity reduction. Considering this dramatic cost difference, ICE-powered vehicle manufacturers cannot compete economically against battery-powered electric vehicle producers.

At a higher level, the task no matter what device powers a vehicle is to ruthlessly control model and model option proliferation. The sales and marketing people are always saying: “If we just had this one more option (paint color, interior trim, exhaust system, gear ratio, blah blah blah), we could sell more vehicles”. But will those (questionable) marginal sales offset the complexity to operations and costs to the product – direct costs and corporate overhead — of adding the desired option(s) and all the new skus they entail? Without constant management attention, over many years the corporate sku counts creeps ever skyward! Commensurately, so do the costs, number of employees, the number of a company’s suppliers, and the time it takes to get anything accomplished.

During GM’s Electric Vehicle Strategy Day press conference on March 4, 2020, GM announced a total of 19 initial [sic!] battery and drive unit configurations for their forthcoming eleven new electric vehicles, comparing that to its 550 internal combustion engine/powertrain combinations they produce today. How can any company make money grappling with that 550-combination complexity and its pernicious effect on cost and time throughout the organization? It is any wonder that GM is so large and cumbersome – so unresponsive!

Battery-powered electric vehicles emit no emissions and thus don’t need to go through the expensive CAFÉ certification process, and require far less total time and manpower to produce. Indeed, a Bloomberg article “They Don’t Need Us Anymore”, dated 9/27/2019, states: “Ford has estimated electric cars will require 30% fewer hours of labor per vehicle and 50% less factory floor space.” I think Tesla would tell you that Ford’s numbers are conservative.

A vivid example of Tesla’s parts count reduction campaign can be found in its new Model Y, in the rear section of the unit body construction. In the almost identical Model 3, according to Munro Associates, this section had between 70 and 100 parts all welded, riveted, or bonded together. Imagine the variety of machines and personnel and time required to carry that process out.

In the Model Y, those 70 plus pieces are replaced by four parts made of beautifully engineered aluminum castings. As a result, the Model Y rear section is far stronger, quicker to assemble, and — even considering the capital cost of the casting equipment — probably an order of magnitude less expensive to produce and install. But Tesla is not content with that improvement. Soon those four aluminum casting pieces will be replaced with a one-piece aluminum casting!

This two-step step function improvement shows that Tesla has matured as a manufacturing company and has learned to design for quality and manufacturability. Using innovative technologies and manufacturing processes, Tesla will be able to vastly improve current models with similar engineering changes, as well as bring out even more competitive new designs. Its new Cybertruck (630,000 orders and counting!) is another revolutionary step forward with regard to these matters.

Photo courtesy Pixabay

Your feedback in the form of comments or suggestions are welcome in the comment window. Thank you for following my blogs on this site and for participating in my blogging community.

2 Responses

Good info. Wonder how many “moving” parts are in an ice versus electric car and how many fluids difference there is?

Bruce

Bruce: Thanks for reading and the comment. Major fluids difference is no engine oil (6 qts), no radiator cooling fluid (average 20 qts), and no transmission fluid (average 14 qts). Typical ICE differential fluid roughly equal to (1) Tesla drive unit fluid. Major difference is maintenance costs — no need to change engine oil and filter every 7,500 miles. Weight difference would be about 75 lbs. TG